Special thanks to Michael Jones and his ministry Inspiring Philosophy for providing the information and sources in this article, as well as to scholars Mark Chavalas and John Walton for their contributions to the video. “We are so far removed from the cultural world of the ancient Near East that there is so much about the Torah we do not understand. This is a deep dive exploring what the Torah was and what it most likely functioned as.” – Inspiring Philosophy (description of the video). I want to be as faithful to the structure in the way in which the information is provided in the video.

The purpose of presenting this information in written format is to make the sources easily accessible on one page. There may be times when you’re in the middle of a discussion about the Bible and need to reference one or multiple sources simultaneously to support your point. Answers for Christ exist to ensure you’re always equipped with solid answers, leaving little to no reason for uncertainty in your responses. (Sources at the Bottom)

Legal Collections

One of the biggest issues brought up with the Bible is the mosaic law within the Old Testament. Why would God command certain forms of capital punishment for minor offenses?

- “2 Work shall be done for six days, but the seventh day shall be a holy day for you, a Sabbath of rest to the Lord. Whoever does any work on it shall be put to death.” – Exodus 35:2 (NKJV)

- “9 ‘For everyone who curses his father or his mother shall surely be put to death. He has cursed his father or his mother. His blood shall be upon him.” – Leviticus 20:9

What does the law contain odd commands that rarely apply?

- “11 If two men fight together, and the wife of one draws near to rescue her husband from the hand of the one attacking him, and puts out her hand and seizes him by the genitals, 12 then you shall cut off her hand; your eye shall not pity her.” – Deuteronomy 25:11-12 (NKJV)

- “13 You shall not have in your bag differing weights, a heavy and a light.” – Deuteronomy 25:13 (NKJV)

Does this reflect God’s moral character or reveal insecurity? The issue lies in interpreting the Mosaic Law through a modern cultural lens. The Torah was not written within a Western framework, but in the cultural context of the ancient Near East. To understand God’s intentions and the purpose of the Torah, we must consider its original historical and cultural setting.

The first thing to recognize when reading the Torah in the Pentateuch is that we often assume it functions as a formal legal code, which is why it is commonly referred to as the Mosaic Law. However, scholars frequently question this assumption. In fact, many argue that this was not the Torah’s intended purpose. Christine Hayes provides a helpful summary of this issue.

“we would do better to understand these materials as legal collections and not codes. I know the word code gets thrown around a lot. Code of Hammurabi, and so on. But they really aren’t codes. Codes are generally systematic and exhaustive and they tend to be used by courts. We have no evidence about how these text were used. In fact, we think it’s not likely that they were really used by courts, but they were part of a learned tradition and scribes copied them over and over and so on. They are also certainly not systematic and exhausted. So for example, the code of Hammurabi. We don’t even have a case of intentional homicide. We only have a case of accidental homicide. We really don’t even know what the law would be in a case of intentional homicide. We can’t really make that comparison with the biblical law” – Christine Hayes, Yale University

Similarly, John Walton refers to ancient Near Eastern legal collections as treatises on judicial wisdom.

“The current view is that the collection of legal sayings in the ancient Near Eastern documents constitutes expressions of legal wisdom assembled under the king’s sponsorship (and attributed to him) to provide evidence of his wisdom and justice… These are not laws that have been enacted, nor necessarily rulings that have actually been given. They are treatises on judicial” – Walton, John H., and D. Brent Sandy. The Lost World of Scripture: Ancient Literary Culture and Biblical Authority. IVP Academic, 2013, p. 218.

Ancient Near Eastern Legal Collections:

- They were more didactic than prescriptive.

- They were trying to teach judicial lessons or express the importance of order and justice.

- There is no indication ancient Near Eastern legal collections were prescriptive or understood as national

“…there is no evidence that any collection of Near Eastern laws functioned as a written code that was applied by a strict method of exegesis to individual cases. As far as we can tell, these bodies of laws served educational purposes and gave expression to what was regarded as just in typical cases, but they left considerable latitude to local courts for determining the right in individual suits. They aided local courts without controlling them.” – Hillers, Delbert R. Covenant: The History of a Biblical Idea. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969, p. 88.

Let’s take some time to examine how other ancient Middle Eastern legal collections functioned. Since our modern culture is so far removed from the ancient world, understanding these legal collections such as the Torah requires careful study.

Jean Bottéro, a scholar who has extensively studied the Code of Hammurabi (1750 B.C.), notes that this Old Babylonian text predates Moses. However, it is inaccurate to refer to it as a “law code” in the modern sense. The king did not establish fixed laws but rather issued decrees. See: Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 156-184.

“It was the Greeks who have taken us further, to the universal concepts, the absolute formulations, that allow us the clear perception and the distinct expression of the principles and the laws in all their abstraction.” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, p. 178.

– LeFebvre refers to the cultures of the ancient Near East as non-legislative societies.

…a fundamental distinction can be discerned between essentially legislative (e.g. classical Athens) and essentially non-legislative (e.g. the cuneiform literature) law writings.” – Lefebvre, Michael. Collections, Codes, and Torah: The Re-Characterization of Israel’s Written Law. Cambridge University Press, 2006, pp. 23

“A word for ‘law’ doesn’t even exist in their language!” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 156-184

No one would have read this inscription and assumed it was an attempt to establish universal legislation for all people under Hammurabi’s rule. This does not mean laws, as we understand them today, did not exist; rather, as Bottéro notes, they were unformulated.

“There were undoubtedly “laws,’ but they were unformulated, just as the principles of science remained unformulated.” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 181

What truly mattered was maintaining order, and it was the king’s duty to establish and uphold it. He achieved this through his decrees, which his subjects were required to follow.

Ancient Near Eastern Legal Collections:

- The concept of justice was a means to an end.

- They didn’t care about justice for justice’s sake or ethics for the sake of doing good.

- They cared about establishing and maintaining order.

Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 156-184

For example, in today’s world, we would prioritize equality under the law over maintaining order. If the president were guilty of murder, we would prefer that he stand trial and face the consequences of the law. However, such a process could lead to disorder, causing turmoil within the nation. In contrast, the Babylonians viewed the preservation of order as the highest good. From their perspective, a process that disrupted order such as a leader facing trial would be considered a disaster. For them, it would have been better for the leader to escape punishment than to go to prison, as the resulting disorder would be seen as more harmful than the crime itself. This reflects the Babylonian understanding of justice, which was less about ethical considerations and more about promoting and maintaining order. For instance, it would be seen as a greater offense for a prostitute to leave the brothel and disrupt the social order than for the act itself. In modern terms, we might view such an act as a positive change, even if it disrupts societal norms. The Babylonians used two words (kittu u mêsaru) to express justice, which, when combined, likely meant “to establish firmly and maintain order.”

The king issued decrees to maintain order, as demanded by the gods. Therefore, ancient Eastern legal collections were not necessarily intended as laws for the people to follow, but rather as divine commands.

“The ‘Code’ of Hammurabi is essentially a self-glorification of the king.”

– His subjects would have read it as descriptive justice, not prescriptive justice.

– It was meant to display his wisdom by explaining what justice looked like through what were most likely hypothetical

cases, or “models to be considered in a spirit of analogy.” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 178-183

Some scholars suggest that the law originated from real cases and actual decisions rather than hypothetical scenarios. While this is plausible, it doesn’t necessarily imply that these cases established universal laws for future situations. Instead, they likely served as models for future judges to learn from, as Walton argues.

“[Legal treatises] serve as manuals that are compiled to teach principles to practitioners through paradigms. They instruct by circumscribing the field of knowledge with examples.” – Walton, John H. Introducing the Conceptual World of the Hebrew Bible: Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament. 2nd ed., pp. 271.

A helpful comparison might be drawn to elementary school math problems. When we were children learning math, we were often taught through hypothetical scenarios, such as: “If Jim has 12 apples, Sally has 4, and Tim has 5, how many apples does Jim have left?” These questions were not trying to teach economics or prescribe any actions, nor were they based on real events. Instead, they served to teach and explain mathematical concepts through hypothetical cases.

A more relevant example, in the context of ancient legal collections, could be modern sayings of wisdom such as:

- “Don’t count your chickens before they hatch.”

- “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush.”

- “Don’t keep all your eggs in one basket.”

If these sayings were compiled in a book, we wouldn’t view them as laws to be followed, but rather as wisdom meant to provoke thought. For instance, if someone were carrying all their eggs in one basket instead of spreading them across two, we wouldn’t consider them to have broken any law or committed an ethical violation. Though the advice may appear prescriptive, its purpose is not to mandate actions but to encourage reflection on better practices. Similarly, the Code of Hammurabi functions more like thisproviding models for thinking about justice, rather than imposing modern-style legislation. It was intended to inspire reflection on what justice looks like, rather than prescribing specific actions.

“A law applies to details; a model inspires-which is entirely different.In conclusion, we have here not a law code, nor a charter of a legal reform, but above all, in its own way, a treatise, with examples, on the exercise of judicial powers.” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 167

The Torah likely functioned in a similar way, often translated as “law,” but this does not fully capture its meaning. The term “Torah” actually refers to “instruction” or “teaching,” emphasizing guidance rather than rigid legal prescriptions.

“…tôrâ is much more than mere law. Even the word itself does not indicate static requirements that govern the whole of human experience… The meaning of tôrâ, then, is directional teaching or guidance for walking on the path of life.” – Bansen, Greg L., Walter C. Kaiser Jr., Douglas J. Moo, Wayne G. Strickland, and Willem A. VanGemeren. Five Views on Law and Gospel. Previously titled The Law, the Gospel, and the Modern Christian, Counterpoints, pp. 192-193.

John and J. Harvey Walton argue that the Torah is more about providing guidance to Israel on how to live in holiness and order, rather than prescribing specific actions or consequences. A better way to understand the Torah is to view it similarly to the Book of Proverbs, which doesn’t necessarily prescribe actions, but teaches wisdom and how to think about morality. One of the most well-known proverbs, for example, is found in Proverbs 26:4-5.

- “4 Do not answer a fool according to his folly, Lest you also be like him. 5 Answer a fool according to his folly, Lest he be wise in his own eyes.” – Proverbs 26:4-5

These two statements are clearly contradictory, yet neither is a prescription for dealing with a fool. Instead, the saying teaches about the nature of both a fool and a wise person. The message is that you cannot win with a foolish person, but a truly wise person understands the nature of such circumstances. Similarly, Proverbs 13 is often misunderstood as prescribing specific actions, but this is not always the case. For example, verse 22 reads…

- “A good man leaves an inheritance to his children’s children, But the wealth of the sinner is stored up for the righteous.” – Proverbs 13:22 (NKJV)

This does not imply failure. If you are unable to leave an inheritance for your grandchildren, it may be wiser to direct that inheritance to charity, especially if your children are corrupt or worse off than you were. It is simply a piece of wisdom that does not apply to every situation, nor is it intended for all people.

Similarly, a few verses later, it says…

- “He who spares his rod hates his son, But he who loves him disciplines him promptly.” – Proverbs 13:24 (NKJV)

This is not prescribing that you literally beat your son with a rod. Rather, it is metaphorically teaching that, if you are wise, you will discipline your children in the proper manner. This passage, like many others, uses metaphorical language to convey deeper principles. The very next verse further illustrates this point.

- “The righteous eats to the satisfying of his soul, But the stomach of the wicked shall be in want.” – Proverbs 13:25 (NKJV)

This is not suggesting that sinful people are always hungry, but rather metaphorically teaching that it is better to be content with what you have than to be consumed by greed, constantly chasing after the next best thing. Proverbs, then, is not necessarily prescribing specific actions. Instead, it teaches us how to think and understand morality and wisdom. We are meant to approach Proverbs holistically selecting isolated verses and applying them individually does not fully capture the intent. To truly understand wisdom, we must apply the entire book and consider the circumstances in which we live.

Similarly, given the ancient Eastern cultural context, the Torah is teaching what justice looks like, not prescribing specific actions. It offers a description of justice and order for Israel within their cultural framework. Like Proverbs, the Torah is meant to be understood holistically. The compilers did not intend for isolated sections to be taken out of context. For example, you cannot understand the passages on slavery without reading them in light of the broader themes of loving the stranger and caring for the poor and underprivileged.

- “15 ‘You shall do no injustice in judgment. You shall not be partial to the poor, nor honor the person of the mighty. In righteousness you shall judge your neighbor.” – Leviticus 19:15 (NKJV)

- “35 ‘You shall do no injustice in judgment, in measurement of length, weight, or volume.” – Leviticus 19:35 (NKJV)

- “35 ‘If one of your brethren becomes poor, and falls into poverty among you, then you shall help him, like a stranger or a sojourner, that he may live with you.” – Leviticus 25:35 (NKJV)

Israel was meant to understand the Torah as a whole, not as isolated sections. Skeptics often point out contradictions within the Torah, but this is not a problem if the stipulations are didactic rather than prescriptive. For example…

- 22 ‘When you reap the harvest of your land, you shall not wholly reap the corners of your field when you reap, nor shall you gather any gleaning from your harvest. You shall leave them for the poor and for the stranger: I am the Lord your God.’ ” – Leviticus 23:22 (NKJV)

But…

- 19 “When you reap your harvest in your field, and forget a sheaf in the field, you shall not go back to get it; it shall be for the stranger, the fatherless, and the widow, that the Lord your God may bless you in all the work of your hands.” – Deuteronomy 24:19 (NKJV)

Doesn’t mention the poor…

However, neither of these verses are prescriptive instructions on how to harvest, so they do not contradict each other. Instead, both verses aim to teach a general principle about how to live specifically, how to ensure that the less fortunate are provided for. This is the mindset you should adopt when reading the Torah: not seeking specific laws for every individual circumstance, but understanding the broader principles it teaches.

“[ANE Codes] all seem to have been composed for the same purpose: they are essentially practical and didactic.” – Bottéro, Jean. The “Code” of Hammurabi. Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods, The University of Chicago Press, 2002, pp. 177

This means that the principles within the Torah express the moral importance of certain actions, rather than being prescriptive instructions on how to act in specific situations. The Torah emphasizes ethical values and guides behavior, but it does not always provide rigid prescriptions for every incident.

“…one can propose that these are not laws (i.e., legislation) but selected samples that can serve the intended didactic function. It is in this sense that they offer model justice… They offer sample wisdom; they do not prescribe laws.” – Bansen, Greg L., Walter C. Kaiser Jr., Douglas J. Moo, Wayne G. Strickland, and Willem A. VanGemeren. Five Views on Law and Gospel. Previously titled The Law, the Gospel, and the Modern Christian, Counterpoints, pp. 192-193.

For example, Exodus 35:2 is not necessarily prescribing the death penalty for anyone who works on the Sabbath. Rather, it lists the maximum punishment that could be applied while emphasizing the moral importance of the Sabbath and what justice would look like if it were broken. It describes how justice should be administered in Israel, where the people are in covenant with God. It does not imply that Sabbath breakers should be executed indiscriminately, but instead highlights the reverence with which the Sabbath should be treated by the Israelites. Again…

“…there is no evidence that any collection of Near Eastern laws functioned as a written code that was applied by a strict method of exegesis to individual cases. As far as we can tell, these bodies of laws served educational purposes and gave expression to what was regarded as just in typical cases, but they left considerable latitude to local courts for determining the right in individual suits. They aided local courts without controlling them.” – Hillers, Delbert R. Covenant: The History of a Biblical Idea. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969, p. 88.

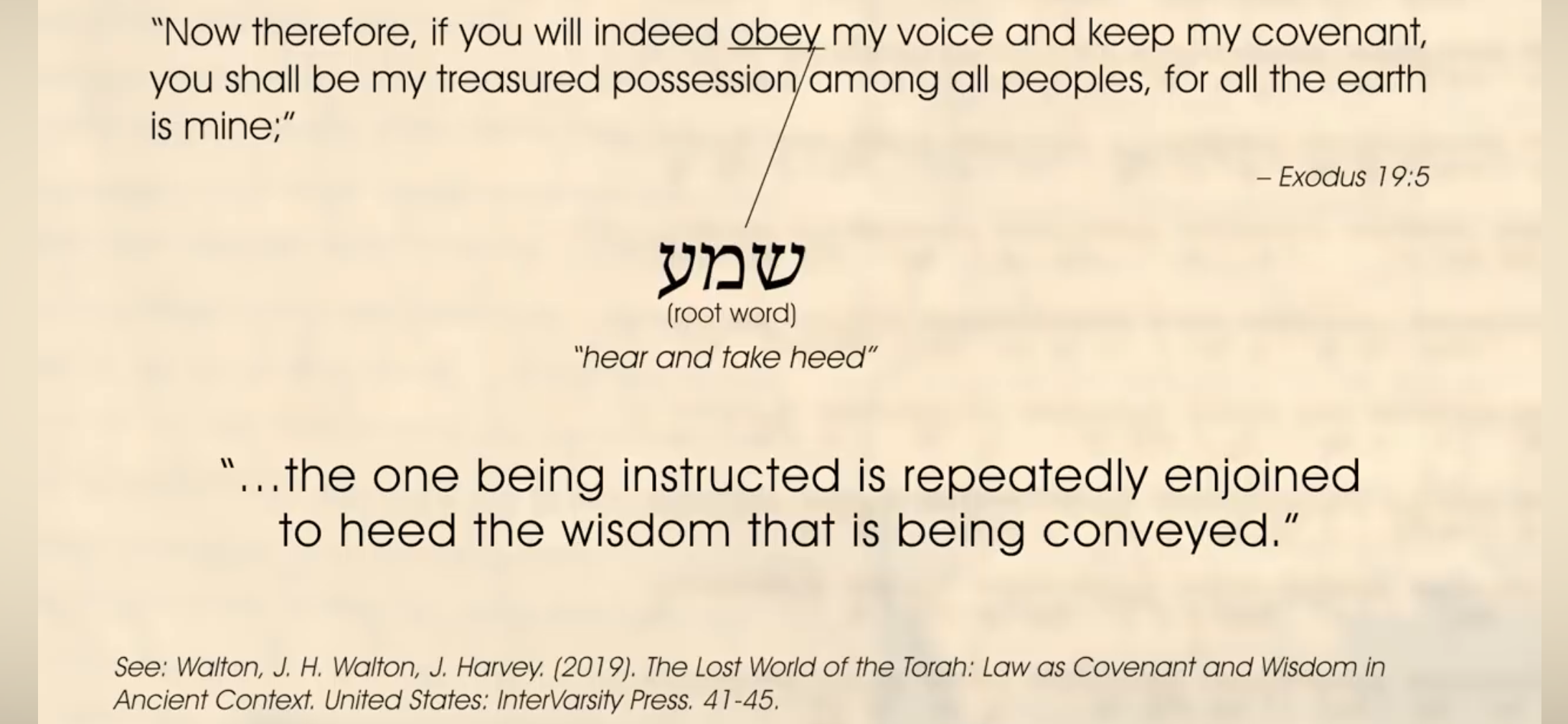

This is supported by Hebrew we often translated. The word obey is us in our English translations, but John and J Harvey Walton note the Hebrew word more likely refers to the one being instructed is repeatedly joined to the wisdom that is being conveyed.

Just as Proverbs offers guidance on how to live a moral life, the Torah also provides guidance—not strict laws. In other words, to live in covenant with God requires embracing wisdom, and ignoring it comes with peril.

“The expected response to the Torah is far different from a response to legislation. Legislation carries a sense of ‘you ought to,’ while instructions carry a sense of ‘you will know.'”

This doesn’t mean the Torah never prescribed rules of conduct or that punishments were never applied. To claim this would be an oversimplification. In some cases, the Torah does offer clear prescriptions for conduct and consequences. However, once we understand the overarching wisdom of the Torah, we learn how and when to apply it appropriately. Similarly, understanding the wisdom of Proverbs allows us to discern how to apply its teachings in different circumstances.

One might view the law as an ideal standard, but with the understanding that this ideal is rarely fully realized. For example, the Bible describes God as slow to anger, allowing Israel time to repent instead of immediately acting in punishment, even though He had the right to do so (Exodus 34:6; Nehemiah 9:17; Nahum 1:3). This suggests that punishments were not always carried out, even when they could have been.

In other words, Exodus 35:2, as part of the Torah, is emphasizing the moral importance of the Sabbath so important that its violation could warrant death. However, this does not mean that Sabbath breakers should always be executed. The maximum punishment listed could be applied at the discretion of the judge, based on the specific circumstances. Instead, it underscores the value of the Sabbath and how crucial it was for Israel to honor it within their covenant with God. Yet, this ideal was not always reflected in practice.

We see this reasoning play out in a later narrative. In 2 Samuel 12, when King David commits adultery with Bathsheba and has Uriah killed, the death penalty is prescribed, in line with the Torah’s punishment for adultery and murder. Yet, the text shows that later Israelites did not necessarily view Torah punishments as universal or strictly prescriptive.

This misunderstanding of the Torah is also reflected in the teachings of Jesus. Jesus seemed to understand that the law could not always be applied rigidly, depending on the circumstances. His contemporaries often interpreted the Torah as unbreakable legislation, but Jesus recognized that certain aspects held greater importance than others.

In Matthew 12, Jesus allows His disciples to pick grain on the Sabbath, which the Pharisees criticize, claiming, “Look, your disciples are doing what is not lawful to do on the Sabbath” (Matthew 12:2). But Jesus responds by citing narrative passages outside the Pentateuch, showing how early Israelites understood the teachings about the Sabbath (Matthew 12:3-8).

From Christ’s teaching, we can discern two key points: First, He did not view the Torah as prescribing unbreakable laws about the Sabbath that required punishment. Instead, He understood the Torah as offering wisdom and guidance, meant to point to something more important—living rightly with God. Second, it was about drawing the proper principles from the Torah, not adhering to rigid laws, as J. Daniel Hayes noted.

“In essence the Pharisees criticized Him with the details of the Law, but Jesus answered them with principles drawn from narrative.” – J. Daniel Hays, “Applying the Old Testament Law Today,” Bibliotheca Sacra, 158 (January – March 2001), 21-35

“Jesus appeals instead to inspired narrative to show how God expected the legal statements to be qualified in practice, ‘a precedent for allowing hunger to override the law’ (Sanders 1990:20)…Jesus challenges not merely their interpretation of the Sabbath but their entire method of legal interpretation.” – Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. pp. 355.

Jesus reminds the Pharisees of the need to remember mercy when applying the Torah. The Torah is primarily descriptive of what justice and holiness should look like, but justice was not always meant to be applied in a rigid manner. God teaches us that we should prioritize mercy whenever possible, rather than assuming that the Torah demands unbreakable laws to define justice.

“Not merely human life but human need in general takes precedence over regulations. Kindness towards others’ genuine need — for example, that of hungry disciples — precedes rules whose purpose was to please the God who values such kindness more highly (12:7; 9:13; cf. 4:2).” – Keener, Craig S. The Gospel of Matthew: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary. pp. 357.

Israel was meant to read the wisdom of the Torah to understand what justice and holiness look like. However, Jesus reminds us that God desired Israel to apply mercy and understanding whenever possible, rather than assuming the Torah required unending punishments. The Torah expresses the moral importance of various actions to help Israel grasp how significant they were to God within their covenant with Him. It is not simply a moral code for all people in all times and places, but rather a set of covenant stipulations between God and Israel. While it contains moral principles, they are specifically relevant to Israel’s relationship with God. Unlike other Ancient Near Eastern legal collections, the Torah functions as part of what we would call a suzerain-vassal treaty.

- A Suzerain treaty is where a king would take on another nation as a vassal.

- The Suzerain or Lord would establish what the vassal would now need to do to please their new overlord in the form of stipulations.

- Then the Suzerain would include what blessings they would receive if they were loyal and what curses would fall on them if they were not.

Hillers, Delbert R. Covenant: The History of a Biblical Idea. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1969, p. 46-71.

When the suzerain imposed a stipulation, he was not asserting law; he was extending his identity and realm through the vassal. The stipulations were not meant to be exhaustive, covering every aspect of life, but were instructions on how to reflect the suzerain’s character. These stipulations served as examples to help the vassals understand how to be loyal, but the loyalty was meant to extend beyond the stated examples.

It’s like teaching martial arts: I would show you how to properly kick, punch, and block. However, I’m not teaching you specific moves for every situation, nor am I instructing you to go out and fight. Instead, I would be teaching you how to think about fighting and how to respond to potential situations. As your instructor, my goal would be for you to know when to defend yourself or when to call for help not to prescribe fighting but to teach you how to approach it. Similarly, a vassal’s loyalty extended beyond the stipulations it was about understanding what loyalty meant, how to think about it, and how to represent the suzerain.

Likewise, the Torah was primarily about teaching Israel how to be a holy people and properly represent the Lord before the surrounding nations. It wasn’t a moral code for all people in all times, but instructions for how Israel could reflect God’s character in their cultural context. It was not intended as an ideal system, but a culturally situated framework designed to enhance the reputation of the Lord among the nations of the ancient Near East. The Torah’s goal was not to address modern issues like slavery or create a perfect moral code it was tailored to the cultural and ethical realities of Israel’s time.

In essence, the Torah was meant to teach Israel how to live in God’s presence in the land of Canaan, providing hypothetical cases that described, rather than prescribed, what an orderly and holy life should look like for Israel as God’s vessel. It was about enhancing the name of the Lord in their specific cultural context, not setting up an ideal system for all people, in all places, at all times.

“If the Torah gives illustrations of ways that order can be maintained in the society of ancient Israel-covenant order defined by preserving the sanctity of sacred space as God’s —it is all culturally relative.” – Walton, John H., and J. Harvey Walton. The Lost World of the Torah: Law as Covenant and Wisdom in Ancient Context. 1st ed., InterVarsity Press, 2019, p. 100.

The Torah is culturally dependent and serves as descriptive wisdom on how to live as God’s vessel. We should not be surprised by its lack of focus on certain moral issues that we face today, as these were never its intended concerns. Its primary purpose was to teach Israel how to properly represent the Lord before the ancient nations of the East, who were not grappling with the same moral questions we are now. Rather than being prescriptive, the Torah functions more like Proverbs, guiding Israel on how to think about justice, act with wisdom, and maintain order in God’s presence. Most importantly, it is not a law code or legislation. What we have in the Torah is a collection of judicial wisdom tailored to Israel’s ancient cultural context, showing them what it meant to be God’s representative and what an orderly, holy people should look like. Once we grasp the Torah’s main purpose, we can better understand how it fits within the larger biblical narrative. It was never meant to be an ideal moral code for all people at all times; it was culturally situated and must be read with that context in mind.

Sources

Sources:

Christine Hayes – Lecture 10. Biblical Law: The Three Legal Corpora of JE (Exodus), P (Leviticus and Numbers) and D: • Lecture 10. Biblical Law: The Three L…

John Walton and Brent Sandy – The Lost World of Scripture

John Walton – Ancient Near Eastern Thought and the Old Testament (2nd Ed.)

Delbert Hillers – Covenant

Jean Bottéro – Mesopotamia: Writing, Reasoning, and the Gods

Michael Lefebvre – Collections, Codes, and the Torah

Walter Kaiser – Five Views on Law and Gospel

Daniel J. Hays – Applying the Old Testament Law Today: http://faculty.gordon.edu/hu/bi/ted_h…

Craig Keener – The Gospel of Matthew: A Soci-Rhetorical Commentary

John Walton & J. Harvey Walton – The Lost World of the Torah

Your blog is a beacon of light in the often murky waters of online content. Your thoughtful analysis and insightful commentary never fail to leave a lasting impression. Keep up the amazing work!

Would love to perpetually get updated outstanding website! .

I’d have to examine with you here. Which is not one thing I usually do! I take pleasure in reading a post that may make folks think. Additionally, thanks for permitting me to comment!

Hi my loved one! I wish to say that this post is awesome, nice written and include almost all important infos. I’d like to peer more posts like this .

Hi! I just wanted to ask if you ever have any trouble with hackers? My last blog (wordpress) was hacked and I ended up losing several weeks of hard work due to no back up. Do you have any solutions to prevent hackers?

I have been checking out many of your stories and it’s nice stuff. I will surely bookmark your website.

It’s really a nice and helpful piece of information. I am glad that you simply shared this useful info with us. Please keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles. I’ll bookmark your weblog and check again here regularly. I am quite sure I’ll learn many new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

I am impressed with this site, really I am a big fan .

I’m still learning from you, but I’m making my way to the top as well. I absolutely enjoy reading all that is written on your blog.Keep the aarticles coming. I enjoyed it!