By AC

This information is provided to give you a foundational understanding of the origins of the Dead Sea Scrolls. In 2012, some articles were published with sensational headlines like, “The Dead Sea Scrolls Are Forgeries,” designed to provoke shock and grab attention. Unfortunately, many people either didn’t read the full content of articles 1 and 2 or intentionally spread misinformation about them. The confusion largely stems from misleading headlines, which can create a paradigm shift for readers without offering proper context. For a more accurate perspective, here is an interview (starting at the 16-minute mark) hosted by Mike Winger with biblical scholar Wesley Huff.

Sited: Abegg, Martin Jr., Flint, Peter, and Ulrich, Eugene. The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible: The Oldest Known Bible Translated for the First Time into English. HarperOne, 1999, pp. xiv-xvi. (Introduction)

Discovery of the Scrolls:

Between 1947 and 1956, eleven caves were discovered in the region of Khirbet Qumran, about a mile inland from the western shore of the Dead Sea and approximately fourteen miles east of Jerusalem. The eleven caves yielded various artifacts (especially pottery) and manuscripts written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek, the three languages of the Bible. (The Hebrew Bible is written in Hebrew and Aramaic; the Septuagint and New Testament in Greek.)

In addition to the finds at Khirbet Qumran, several manuscripts were discovered at other locations in the vicinity of the Dead Sea, especially Wadi Murabba’at (1951-52), Nahal Hever (1951-52 and 1960-61), and Masada (1963-65).

Description and Contents of the Scrolls:

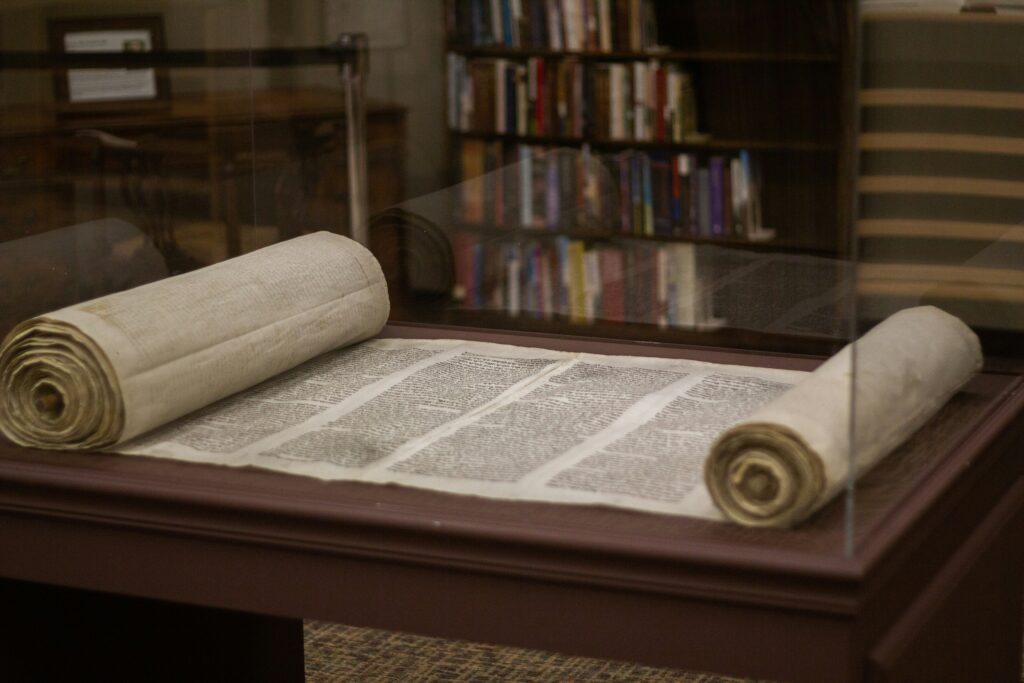

At Qumran, nearly 900 manuscripts were found in some twenty-five thousand pieces, with many no bigger than a postage stamp. A few scrolls are well preserved, such as the Great Isaiah Scroll from Cave 1 (1QIsa*) and the Great Psalms Scroll from Cave 11 (11QPsa*). Unfortunately, however, most of the scrolls are very fragmentary. The earliest manuscripts date from about 250 BC, while the latest ones were copied shortly before the destruction of the Qumran site by the Romans in 68 CE. Approximately forty-five more manuscripts were discovered at the other sites: about fifteen at Wadi Murabba’at, eighteen at Nahal Hever, and twelve at Masada.

Scholars divide the Dead Sea Scrolls into two categories: the “biblical” manuscripts and the “nonbiblical” ones. Of course, this distinction is from our later viewpoint (and not necessarily that of the ancient copyists), but it is useful for purposes of organization and editing. The nonbiblical scrolls are already available in English translation: for example, The Dead Sea Scrolls, by Michael Wise, Martin Abegg, Jr., and Edward Cook (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 1996). But until now the biblical scrolls have never been translated into any modern language; The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible makes this material available in English for the first time.

Some 215 manuscripts from Qumran, plus twelve more from the other sites, are classified as biblical scrolls, since they contain material found in the canonical Hebrew Bible. Since these manuscripts contain the texts from which The Dead Sea Scrolls Bible has been translated, they will be discussed in greater detail later in this Introduction (see section headed “The Biblical Scrolls”).

A few brief comments on the nonbiblical scrolls will be helpful at this point. There are approximately 670 of these scrolls, which can be divided into five groups: (1) rules and regulations (for example, the Community Rule); (2) poetic and wisdom texts (for example, the Hodayot or Thanksgiving Psalms); (3) reworked or rewritten Scripture (for example, the Genesis Apocryphon); (4) commentaries or pesherim (for example, the Pesher on Habakkuk); and (5) for example, the Copper Scroll.

The nonbiblical scrolls can be very helpful for understanding Scripture at Qumran, since they often quote from or refer to biblical books and passages.These manuscripts also offer valuable insights into how Scripture was used and interpreted by the Essenes and other Jewish groups in the last few centuries BCE and up to the destruction of the Qumran community in 68 CE. Many of these documents are also of direct relevance to early Judaism and emerging Christian-ity, since they anticipate or confirm numerous ideas and teachings found in the New Testament and in later rabbinic writings (the Mishnah and Talmud).

Origin of the Scrolls

Most scholars agree that the group who lived at the Qumran site from about 150 BCE to 68 CE was a strict branch of the Essenes. Together with the Pharisees and Sadducees, the Essenes formed the three main divisions (or “denominations”) of Judaism at the time of Jesus; they were previously known to us in works of the Hellenistic Jewish writers Josephus and Philo, and of Latin authors such as Pliny the Elder. It is also generally agreed that these Essenes deposited many scrolls in most of the Qumran caves. However, a smaller number of scholars disagree with these points. It has been suggested, for instance, that the members of the Qumran community were not Essenes at all but Sadducees, or that the site was in fact a military fortress or a winter resort.

These issues are of great importance for understanding the nonbiblical scrolls, since scholars distinguish between those manuscripts that were composed at Qumran and those that came to the Qumran “library” from elsewhere. Many scholars refer to the writings composed at Qumran as the “sectarian” scrolls, which is helpful for purposes of identification—but is also confusing. In modern Judaism and Christianity, a “sect” is usually an offshoot of a larger religion and is frequently viewed as eccentric or deviant with respect to beliefs. But both scholars and laypeople would do well to remember that during the entire Qumran period, the Pharisees and Sadducees were as much “sects” as the Essenes were! It was only from the second century CE onward that one type of Judaism—that of the Pharisees and their descendants, the Rabbis—became standard for the Jewish people as a whole.

These issues are of less importance with respect to the biblical scrolls. For one thing, all scholars agree that none of the biblical texts (such as Genesis or Isaiah) was actually composed at Qumran; on the contrary, they all originated before the Qumran period. It is also widely held that many or most of these manuscripts were brought to Qumran from outside and were thus copied elsewhere. This means that the value of most biblical scrolls lies not in establishing precisely where they were written or copied, but rather in studying the textual forms they contain.

Several distinctive biblical scrolls, however, were copied at Qumran, which raises some interesting issues. For example, it is likely that 4QSama was copied there, since it was copied by the same scribe who penned the main manuscript of the Community Rule (1QS). This offers helpful insights into scribal habits among the Qumran community. Another issue is whether or not such Qumran scribes modified the text they were copying in order to produce distinctive Qumranic readings of the biblical text. The evidence to date suggests that such alteration did not take place.

I couldn’t leave without mentioning how much I enjoyed your content. I’ll be back to check out your new posts regularly. Keep up the awesome work!